Gifting Decisions and Planning with Flexibility Under OB3*

By Kim Kamin, JD, AEP® (Distinguished) and Jonathan Lee, JD†

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

The One Big Beautiful Bill Act of 2025 (“OBBA” or “OB3”) raises federal transfer tax exemptions in 2026 to $15 million (USD) per individual, to continue to be indexed for inflation annually in subsequent years with no scheduled sunset. Exemptions at this level present significant planning opportunities for ultra-high-net-worth families capable of leveraging the current levels through lifetime gifting. This paper encourages advisors to move away from fear-based “use it or lose it” rhetoric that has been heard in the past, focusing instead on thoughtful client-centered planning and best practices. These include maximizing exemption use by gifting to grantor trusts, ensuring flexibility through trust protectors and powers of appointment, and structuring for adaptability across jurisdictions. The paper promotes a resilient tailored approach to estate and tax planning—one that stays aligned with a family’s long-term objectives as laws continue to evolve.

INTRODUCTION

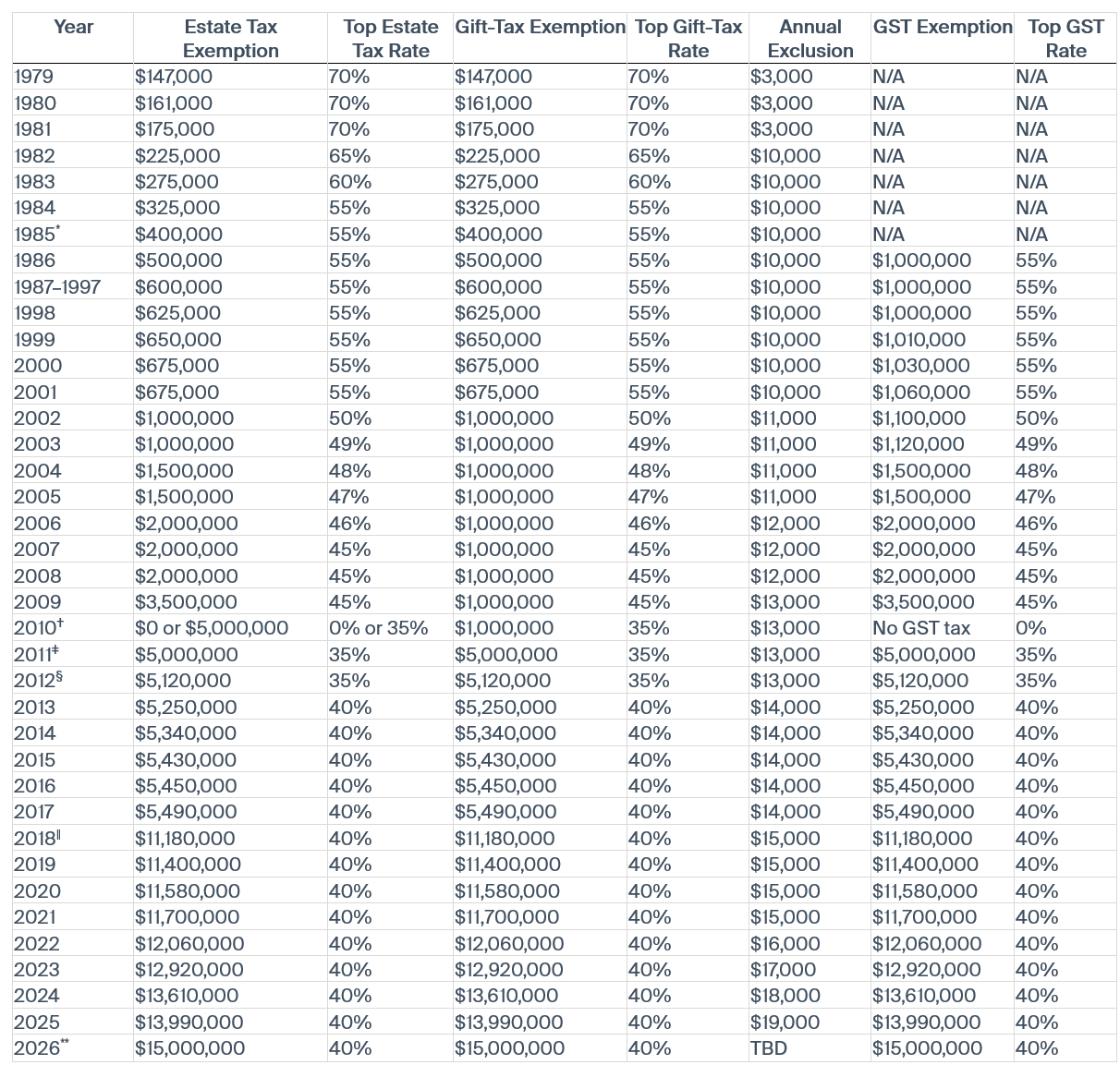

Under the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 (TCJA),1 federal transfer tax exemptions are currently at a historic high of $13.99 million per individual (see Addendum 1).2 With the enactment of the One Big Beautiful Bill Act (“OBBBA” aka “OB3”),3 on January 1, 2026, exemption amounts will increase to $15 million per individual, and exemptions will continue to be indexed for inflation in future years.4 The ability of a married couple to shelter $30 million from transfer taxes cements the notion that only families with at least $30 million are considered ultra-high-net-worth.

On July 4, 2025, the president signed the OB3, which increases the exemption amount indefinitely and adjusts it annually for inflation. The indefinite extension of the expiring TCJA estate tax provisions is projected to reduce federal tax revenue by more than $240 billion between 2025 and 20345 and in total the new law increases the overall deficit to approximately $3.8 trillion.6

The approach for advisors remains unchanged. Clients who can afford to take advantage of the current gift and generation-skipping transfer (GST) tax exemption levels should utilize these high levels now rather than waiting until death. Meanwhile, clients who cannot afford to make such gifts should never feel pressure to do so.

AVOIDING FEAR TACTICS

In the past, when exemptions were threatened, discourse around planning often centered on the warning of “use it or lose it.” Emphasizing that inaction could lead to the loss of something valuable creates a false sense of urgency and can cause clients to make hasty decisions.7

In 2012 and again in 2021, many may recall that this urgency led some clients to execute hastily drafted trust agreements. The results were often funded, irrevocable trusts with poor terms and limited flexibility. Worse still, this type of psychological framing proved false because exemptions did not, in fact, decrease.

The risk with fear tactics is that clients may become skeptical and less willing to act in the future if the negative predictions fail to materialize. Now that OB3 has become law, the buildup over the past two years serves as another example where clients might believe that concerns about exemption levels sunsetting were greatly exaggerated and efforts to induce fear were premature. That said, congressional debate leading up to the OB3 was highly polarized, and future developments could range from a full repeal of the estate tax to the introduction of a new wealth tax. No one knows for certain what the transfer tax rules will be in the future.

Therefore, instead of pressuring clients, advisors should work with them to embrace the current tax structure and any future legislative changes as an opportunity to engage in thoughtful wealth transfer planning.

PLANNING FOR APPROPRIATE CLIENTS

For billionaire and centimillionaire clients, the desirability of gifting at current exemption levels should be fairly straightforward. For ultra-high-net-worth clients with less wealth, the choice is not as clear. The reality is that even families with $30 to $50 million in assets can expect liquidity and cash-flow needs that may impede their ability to make full exemption gifts. Whether large gifts are prudent depends on many factors, including a client’s age, earning potential, investable asset base, and spending needs.

Advisors should assess each client and family’s unique circumstances when making gifting recommendations. For clients with significant wealth, however, it is typically still advantageous for them to gift now to a GST-exempt grantor trust that can grow without an income-tax drag between the time of funding and the client’s death rather than waiting to use available exemptions to fund a GST-exempt family trust at the time of death.

For example, as shown in Figure 1, if a client gifted in 2025 and lived another 20 years, under the conservative assumption that the trust assets grow at an average of 5 percent per year with no income-tax drag, they would have successfully appreciated more than $37 million out of their estate. If the client waited until death (accounting for inflation adjustments), the amount would be closer to $20 million.

FIGURE 1: FUNDING GST-EXEMPT FAMILY TRUST IN 2025 VS. 2045 (WITH 5% AVERAGE GROWTH)

Figure 1 illustrates the amount of GST-exempt assets that would be available in trust for descendants if the client died in 20 years and (1) waited to transfer GST exemption at death or (2) applied full GST exemption now. Figure 1 assumes: (1) dynasty trust funding as of January 1, 2025 with no spend-down and the client paying all income taxes for the trust, (2) exemption inflation adjustments averaging 2 percent and rounded to the nearest multiple of $10,000 as required under 26 U.S.C. § 2010, (3) growth of the assets at 5 percent, and (4) no other tax law changes impacting the exemptions during the stated time periods. Figure 1 ignores the added benefits of making additional annual gifts of any inflation-adjusted exemption amounts to the dynasty trust each year during life and the benefits of depleting the client’s remaining taxable estate by paying the income taxes for the trust. The authors note that Figure 1 does not capture the increased exemption under OB3. Accounting for the 2026 exemption of $15 million, the amount passing at death above would be equal to $21,850,000. The authors thank Les Carter of Gresham Partners LLC for his assistance with this analysis.

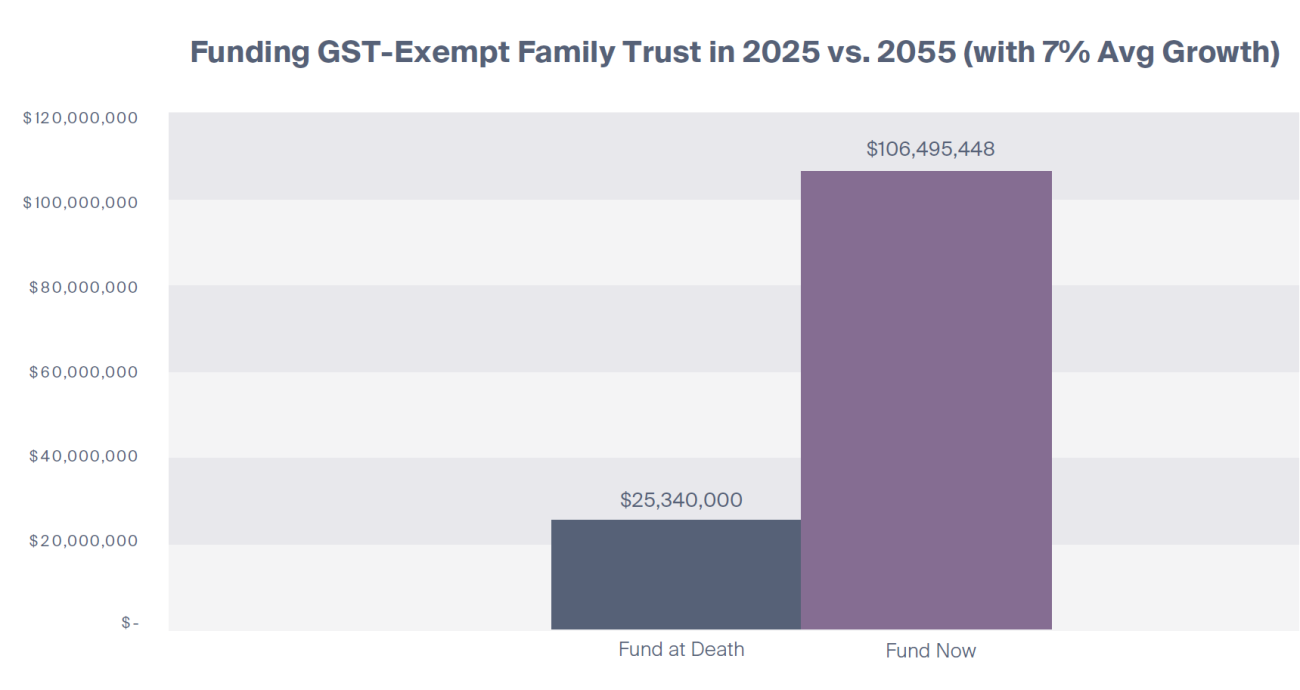

If the client in Figure 1 lived another 30 years with the assets in the GST-exempt trust growing at an average of 7 percent per year with no income-tax drag, the client would have successfully transferred more than $106 million out of their estate. If they waited until death (assuming inflation adjustments), the sum would be less than one-fourth of that amount (see below figure 2).

FIGURE 2: FUNDING GST-EXEMPT FAMILY TRUST IN 2025 VS. 2055 (WITH 7% AVERAGE GROWTH)

Figure 2 illustrates the amount of GST-exempt assets that would be available in trust for descendants if the client died in 30 years and (1) waited to transfer GST exemption at death or (2) applied full GST exemption now. Figure 2 assumes: (1) dynasty trust funding as of January 1, 2025 with no spend-down and the client paying all income taxes for the trust, (2) exemption inflation adjustments averaging 2 percent and rounded to the nearest multiple of $10,000 as required under 26 U.S.C. § 2010, (3) growth of the assets at 7 percent, and (4) no other tax law changes impacting the exemptions during the stated time periods. The illustration ignores the added benefits of making additional annual gifts of any inflation-adjusted exemption amounts to the dynasty trust each year during life and the benefits of depleting the client’s remaining taxable estate by paying the income taxes for the trust. The authors note that Figure 2 does not capture the increased exemption under OB3. Accounting for the 2026 exemption of $15 million, the amount passing at death above would be equal to $26,640,000. The authors thank Les Carter of Gresham Partners LLC for his assistance with this analysis.

With increasing lifespans and access to top-tier healthcare, it is reasonable to assume that a younger client could live another four or more decades and invest at a higher average growth rate during that time. As illustrated in Figure 3, a client who lives another 40 years with assets growing at an average annual rate of 8 percent, with no income-tax drag, would have more than $300 million transferred outside of the taxable estate. In contrast, waiting until death (assuming inflation adjustments) would allow a GST-exempt transfer closer to $30 million. Of course, this is purely hypothetical, as historical exemptions and tax rates suggest that many changes can occur over 40 years.

FIGURE 3: FUNDING GST-EXEMPT FAMILY TRUST IN 2025 VS. 2065 (WITH 8% AVERAGE GROWTH)

Figure 3 illustrates the amount of GST-exempt assets that would be available in trust for descendants if the client died in 40 years and (1) waited to transfer GST exemption at death, without sunset or (2) applied full GST exemption now. Figure 3 assumes: (1) dynasty trust funding as of January 1, 2025 with no spend-down and the client paying all income taxes for the trust, (2) exemption inflation adjustments averaging 2 percent and rounded to the nearest multiple of $10,000 as required under 26 U.S.C. § 2010, (3) growth of the assets at 8 percent, and (4) no other tax law changes impacting the exemptions during the stated time periods. The illustration ignores the added benefits of making additional annual gifts of any inflation-adjusted exemption amounts to the dynasty trust each year during life and the benefits of depleting the client’s remaining taxable estate by paying the income taxes for the trust. The authors note that Figure 3 does not capture the increased exemption under OB3. Accounting for the 2026 exemption of $15 million, the amount passing at death above would be equal to $32,470,000. The authors thank Les Carter of Gresham Partners LLC for his assistance with this analysis.

CONFIRMING CLIENTS’ REMAINING EXEMPTION AMOUNTS

If a client intends to engage in gift planning to maximize their remaining gift and GST exemptions, advisors should exercise caution regarding the actual exemptions. Without a comprehensive understanding of all prior gifts made, there is a risk that future gifts may exceed the exemption limits, triggering a 40 percent gift tax and possibly GST tax. Moreover, prior transfers might have used gift tax exemption without using GST exemption or vice versa. If gifts to a trust exceed a client’s remaining GST exemption, it will cause the undesirable result of a partial inclusion ratio, when a fraction of the trust later is subject to GST tax.

To avoid some of these complications, advisors should consider the following questions:

- How much gift and GST exemptions do the clients have left according to their most recent tax return?

- Did the clients report all their gifts to the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) on their prior Form 709 gift tax returns?

- Have the clients already made annual exclusion gifts that require gift-splitting?

- Is it better not to split gifts so that spouses can use their exemptions separately?

- Do one or more of the clients’ existing trusts have automatic allocation of GST exemption?

To help resolve some of these issues, clients should consult with their attorneys and accountants to ensure they have reviewed the most recent gift tax return. Clients must confirm any unreported transfers to which GST exemption was automatically allocated and any additional gifts that should be reported.

APPLYING REMAINING EXEMPTIONS TO EXISTING TRUSTS

Once the decision to gift is made, and the advisor understands the clients’ situation, determine if any existing trusts may be a suitable receptacle for gifting assets and if such trusts should be modified to better serve the family’s long-term needs. There are several approaches to modifying an existing irrevocable trust.

First, check to see if the trust appoints (or permits someone to appoint) a trust protector who can amend trust provisions to address administrative, tax, investment, or fiduciary issues. Otherwise, “decanting,” or transferring assets from one irrevocable trust to another, may be a desirable approach. Notably, in some states, decanting can be achieved by amending and restating the original trust rather than creating an entirely new one.

As an alternative to decanting, many states also enable the trustee and beneficiaries to modify the existing trust through a nonjudicial settlement agreement (NJSA). NJSAs vary widely among states. Care should be taken both with decanting and NJSAs to avoid shifting interests in a way that arguably causes a taxable gift.8

Before a client modifies an existing irrevocable trust, their attorneys and advisors should help them weigh the following risks: (1) fiduciary exposure, especially when a trustee decants a trust9; (2) modifying a pre-enactment GST trust that was irrevocable as of September 25, 1985, in a way that does not fall under a safe harbor10 or triggers one or more state-specific traps; and (3) any other trust modifications where the IRS might claim that a beneficiary has made a gift to other trust beneficiaries.11

CREATING NEW IRREVOCABLE TRUSTS

If no suitable trust exists, clients may need to create one as soon as it is practical. Many clients may find the idea of transferring assets to an irrevocable trust at current exemption levels daunting. Advisors can ease some of the apprehension by engaging in thoughtful discussion with their clients and addressing the considerations below to draft trusts with maximum flexibility.

A well-crafted trust can address the anticipated needs of the beneficiaries, safeguard their interests across generations, and even contemplate the future needs of a client.

Beneficiaries. Including the spouse, all descendants, and potentially other family members as permissible beneficiaries may be prudent for a GST-exempt trust with substantial assets. When a trust benefits beneficiaries from multiple generations, it is often better to indicate who the primary beneficiary is. For example, the primary beneficiary might be the settlor’s spouse and subsequently each child once the trust has been divided. This allows the trustee to prioritize the interests of each generation while still retaining the ability to extend benefits to grandchildren or more remote descendants when needed.

Distribution provisions. Equally important are the distribution standards. If the trustee is also beneficiary or a “related or subordinate” party,12 distributions must adhere to an ascertainable standard, such as health, education, maintenance, and support. However, provisions also should allow an independent trustee to make distributions under a broader, non-ascertainable standard, such as “best interests.”

Fiduciary succession changes. It also helps when a clear order is set out for who can appoint and remove trustees or other roles. Anticipating a divided trust structure where responsibilities of managing a trust are split among multiple roles at the outset, or allowing one to be created later, further enhances adaptability.

Trust protectors. As referenced earlier, it is always desirable to build in optionality for future modification by permitting the appointment of an independent trust protector who has the power to amend the trust provisions or even to add beneficiaries, if the trust protector is allowed by state law to not be a fiduciary.

Powers of appointment. Clients can build in further flexibility by granting each primary beneficiary special lifetime and testamentary powers of appointment. Powers of appointment are rights that enable the primary beneficiary to direct the disposition of property that is held in the trust either during their lifetime or at death. These powers can be broad and allow the primary beneficiary to appoint assets to any person or organization other than themselves, their estate, or the creditors of either. Assets can be reallocated among loved ones and charity by the primary beneficiary, without causing inclusion in the primary beneficiary’s taxable estate.13

Mergers. Most state statutes permit trusts to merge when they have substantially similar terms. Because the definition of “substantially similar” can be unclear or vary by state, it is helpful to include a provision that permits a merger when trusts are held by the same trustees for the same beneficiaries with similar terms in the trust instrument.

Change of situs and governing law. Because families and their trusts are mobile, a well-drafted trust should permit an independent trustee to change where the trust is administered, i.e., the trust’s situs, and the applicable governing law. When a trust contains this provision, it can be much easier to move states without having to do a full-blown decanting or trust restatement. That said, please keep in mind that the trust duration cannot be extended beyond the original perpetuity period, and there can be other limitations, such as whether the ultimate contingent beneficiary can be modified, depending on the trust.

WINNING WITH GRANTOR TRUSTS

A grantor trust is one where the grantor retains certain powers or control over the trust assets, making the grantor responsible for paying the trust’s income taxes. Using grantor trusts is essential to maximize the benefits of gifting assets that can appreciate outside the donor’s estate during their lifetime without an income-tax drag on the trust’s growth. Notably, grantor trusts always outperform non-grantor trusts in overall financial benefits, even when the grantor resides in a state with income taxes.14

Grantor trusts include certain provisions or powers retained by the grantor, such as the authority to substitute trust assets,15 borrow from the trust without adequate security, and permit an independent trustee to add charitable beneficiaries. A well-drafted grantor trust should also include the ability to terminate the grantor trust status so that the grantor isn’t stuck if the income-tax burden becomes untenable in the future.

It is also helpful to give an independent trustee the power to reimburse the grantor for taxes due on trust income. Currently, seven states, namely Colorado, Connecticut, Delaware, Florida, Indiana, New Hampshire, and New York, have enacted legislation authorizing income-tax reimbursement even for trusts that do not expressly grant trustees the power to do so. Thirteen states, namely Arizona, California, Idaho, Illinois, Iowa, Kentucky, Maryland, Massachusetts, Montana, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, Texas, and Virginia, do not expressly authorize the trustee to reimburse the grantor but have enacted statutes preventing the grantor’s creditors from reaching trust assets based on a trustee’s power to reimburse that is permitted by the trust instrument.16 The trustee’s discretionary power to reimburse, however, should be exercised judiciously and rarely or it could cause arguments for estate inclusion.

BUILDING IN STRUCTURAL OPTIONALITY

Building in structural optionality is also desirable. Here are some ways to structure the trust:

Lifetime family trusts. A GST-exempt lifetime family trust, also known as a dynasty trust, is one of the most common ways to utilize the gift and GST tax exemptions. To signal to clients that trust assets are available to the spouse as a beneficiary during life, if needed, such trusts have become known as spousal lifetime access trusts (SLATs). This approach typically involves one spouse establishing an irrevocable grantor trust with the other spouse as the primary beneficiary and descendants as permissible beneficiaries. If both spouses wish to set up SLATs, advisors must remember the reciprocal trust doctrine. When two trusts are considered too similar, they are treated as if each spouse created a trust for their own benefit, and the assets are included in their estates.17 To mitigate this risk, consider differentiating the following aspects: (1) timing of trust creation and funding; (2) governing jurisdictions; (3) assets and amounts contributed; (4) scope of powers of appointment; and (5) independent trustees or co-trustees. Another option is to structure one of the trusts as a “springing SLAT,” where only the descendants are named as initial beneficiaries, and an independent trust protector can later add the spouse as a beneficiary. Alternatively, the trust could be structured as a “back-end SLAT,” allowing the beneficiary spouse to appoint assets in trust for the donor spouse at death.18

Domestic asset protection trusts (DAPTs). If a client desires to use up their lifetime exemptions, but is worried about permanently losing access to the assets if their fortunes later change, they could create a completed gift trust for the benefit of descendants or other family members, including themselves. This trust should be settled in one of the states that permit DAPTs. Currently, 21 states allow some version of settled DAPTs, namely Alabama, Alaska, Arkansas, Connecticut, Delaware, Hawaii, Indiana, Michigan, Mississippi, Missouri, Nevada, New Hampshire, Ohio, Oklahoma, Rhode Island, South Dakota, Tennessee, Utah, Virginia, West Virginia, and Wyoming.19 Rather than naming the individual as a beneficiary immediately, in some cases it may be preferable to enable a “springing DAPT” by empowering an independent trust protector to later add the settlor as a beneficiary, with distributions to the settlor for health and support needs.

Special power of appointment trusts (SPATs). SPATs are a variation of the springing DAPT or springing SLAT. They enable an “appointer” to exercise a power of appointment in favor of a designated group of permissible appointees. SPATs offer flexibility by allowing the appointer to appoint assets to the settlor (or the settlor’s spouse if not a beneficiary) in the future without making them a beneficiary at the outset.20

When discussing flexibility and optionality with clients, advisors should be mindful of the IRS’ watchful eye. In addition to considering the reciprocal trust doctrine, the IRS may also look for step-transactions. For example, the IRS may determine that one spouse made a gift to the other solely to facilitate that spouse’s immediate gift to a trust for the benefit of the first spouse.21

PROBLEM-SOLVING WITH CREATIVE GIFTING ALTERNATIVES

Not every client who still wishes to take advantage of the current gift-tax exemptions has readily accessible assets to gift. Clients may have sufficient net worth on paper, but portions of their balance sheet may be comprised of assets that are not easily transferable or difficult to value. Other clients may not have the risk tolerance to part with a large portion of their assets in a single year.

With the threat of sunset no longer looming, there is no particular rush to maximize the client’s exemption, but some clients may still be motivated to do so. In such cases, advisors might want to explore creative gifting options, like variations of gifts using promissory notes. For example, a client can secure cash to gift by taking out a commercial loan secured by real estate or other assets.

Alternatively, a client might choose to make an exemption gift to a grantor trust that is at least partly funded with a promissory note. For this planning to work, the debt must be legally binding.22 In such a scenario, the promissory notes should be secured and fully paid during the client’s lifetime to avoid negative income-tax issues when such debt no longer runs between the grantor and grantor trust or disregarded entity.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

Financial advisors should assist suitable clients in maximizing their remaining exemptions now that OB3 has extended and increased the TCJA exemptions indefinitely. Advisors can help shift the discourse away from reactionary, fear-based planning toward thoughtful, meaningful exemption planning. Creating well-crafted, GST exempt grantor trusts with flexibility allows clients to maximize the benefits for their loved ones and respond to changing laws and evolving needs. With the new exemption levels now known, there is no better time to engage in thoughtful, resilient trust planning!

Gresham does not provide tax, legal or accounting advice. The analysis above has been prepared for informational purposes only and is not intended to provide and should not be relied on for tax, legal or accounting advice. You should consult your own tax, legal and accounting advisors before engaging in any transaction.

ADDENDUM: HISTORICAL FEDERAL TRANSFER TAX FACTS

* The GST tax became effective for transfers after September 25, 1985.

† Estates of decedents who died in 2010 had the choice to use the $5-million estate tax exemption/35-percent estate tax rate or $0 estate tax exemption/0-percent estate tax rate coupled with the use of the modified carryover basis rules.

‡ The Tax Relief, Unemployment Insurance Reauthorization, and Job Creation Act of 2010 (TRUIRJCA) provided that the estate tax exemption became portable for married couples in 2011. The American Taxpayer Relief Act of 2012 (ATRA) extended estate tax exemption portability for 2013 and future years.

§ ATRA provided that the estate tax exemption, lifetime gift-tax exemption, and GST tax exemption would be indexed for inflation from 2011 starting in 2012 and future years.

ǁ The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 (TCJA) doubled exemptions and changed inflation adjustments from the traditional Consumer Price Index (CPI) to the Chained Consumer Price Index (C-CPI).

** The One Big Beautiful Bill Act (“OBBBA” or “OB3”) increased exemptions to $15,000,000 beginning in 2026 to be indexed for inflation in future years. The annual exclusion amount for 2026 has yet to be announced.

ENDNOTES

* This piece is derived from Kim Kamin and Jonathan Lee, “TCJA 2.0 Implications for 2025 Gifting: Clients Who Can Afford to Gift Should Do So Now,” Investments & Wealth Review, March/April 2025, which was based on the authors’ article “Do Your Clients Still Want to Plan For 2025 Exemption Gifting?” Trusts & Estates, Vol. 164, No.1, January 2025. The authors gratefully acknowledge Angel Russell-Johnson of Gresham Partners LLC for her assistance in reviewing this article.

† Kim Kamin is a partner and the Chief Wealth Strategist at Gresham Partners LLC, a multifamily office managing more than $10 billion for select families nationally. She is also an adjunct professor at Northwestern University Law School and on faculty for the University of Chicago Booth School of Business Executive Education. She earned a BA with distinction and departmental honors in psychology from Stanford University and a JD from the University of Chicago Law School. Jonathan Lee is an associate wealth strategist at Gresham Partners LLC. He earned a BA in sociology from Syracuse University and a JD from Washington University School of Law.

1. H.R.1 – An Act to provide for reconciliation pursuant to titles II and V of the concurrent resolution on the budget for fiscal year 2018. P.L. 115-97, 115th Congress (2017) (https://www.congress.gov/bill/115th-congress/house-bill/1/text). Adopted 12/22/2017, effective January 1, 2018. This Act is commonly known as the “Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017” or “TCJA.”

2. As shown in “Historical Federal Transfer Tax” (table 1), the statement that transfer tax exemptions have never decreased ignores 2011 when the estate tax and generation-skipping transfer tax were reinstated after being optional in 2010.

3. H.R. 1, 119th Cong. (2025), enacted as Public Law 119‑21 (July 4, 2025). This Act is called the “One Big Beautiful Bill Act” (also known as “OBBBA”, “OB3”, “BBB”, or “OBBB” -but we have it on authority from Justin Miller that the cool kids are calling it “OB3”).

4. H.R. 1, 119th Cong. § 70106 (2025) (changing basic exclusion amount to $15 million). See also Internal Revenue Code (“IRC”) §§ 2505(a) (referencing that the gift exemption is the same as the basic exclusion amount under 2010(c)), 2136(c) (noting GST exemption is same as basic exclusion amount under 2010(c))

5. See E. York and G. Watson, “Making the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act Permanent: Economic, Revenue, and Distributional Effects, Tax Foundation” (February 26, 2025), https://taxfoundation.org/research/all/federal/tax-cuts-and-jobs-act-tcja-permanent-analysis/ (estimates that revenue loss attributable solely to estate taxes over this time period would be $240.5 billion).

6. See G. Watson, H. Li, E. York, A. Muresianu, A. Cole, P. Van Ness, A. Durante, “One Big Beautiful Bill Act” Tax Policies: Details and Analysis” (July 4, 2025), https://taxfoundation.org/research/all/federal/big-beautiful-bill-senate-gop-tax-plan/ (estimates total deficit increase of nearly $3.8 trillion on a dynamic basis over the next decade).

7. See D. Kahneman and A. Tversky, “Prospect Theory: An Analysis of Decision Under Risk,” Econometrica 47, no. 2 (1979). This is referred to by Kahneman and Tversky as “loss aversion” where a real or potential loss is perceived as psychologically more severe than an equivalent gain.

8. See Chief Counsel Advice 202352018, in which the Internal Revenue Service took the position that a beneficiary who consented to a trust modification that added a tax reimbursement clause to a grantor trust had made a taxable gift of unknown value to the grantor. This advice is highly controversial, but it highlights some of the unknown tax ramifications of trust modifications involving notice to beneficiaries.

9. Because trustees have a duty to act in the best interests of all beneficiaries, any decanting that results in harm or change to a beneficiary’s interest or unintended tax consequences may expose the trustee to liability for breach of their fiduciary duty.

10. See 26 CFR § 26.2601-1. Modifying a pre-enactment trust may cause it to lose its GST status, potentially triggering tax liabilities on transfers made to beneficiaries who are two or more generations below the grantor.

11. See Chief Counsel Advice 202352018, described in Note 8 above.

12. IRC § 672(c).

13. Below is an example of desirable language that advisors should look for in the trust instrument:

If the primary beneficiary is living on the creation of a trust, then at such time at or after the date of the creation of the trust as the primary beneficiary has reached the age of [thirty] years, the trustee shall also distribute to such one or more persons or organizations as much or all of the principal of the trust as the primary beneficiary from time to time may appoint either by will, by revocable living trust, or from time to time by signed instrument delivered to the trustee during the primary beneficiary’s life or upon the primary beneficiary’s death, which instrument shall specify whether such appointment is to be effective immediately, upon the primary beneficiary’s death, or at some other time, and which shall be irrevocable unless made revocable by its terms. Notwithstanding the foregoing, the primary beneficiary shall not have the power to appoint any principal under this paragraph to the primary beneficiary, the primary beneficiary’s estate, or the creditors of either, or to satisfy any legal obligation of such beneficiary, including any obligation to support or educate any person.

14. See D. A. Handler and T. R. Meyer-Mangione, “Who Wins When? An Analysis of the Techniques that Use Grantor Trusts to the Techniques that Use Non-Grantor Trusts,” 50th Annual Notre Dame Tax and Estate Planning Institute (September 27, 2024) (modeling demonstrated that under all state income-tax rates now in effect, a grantor trust will always beat a non-grantor trust for overall value to the family, and a state income-tax rate of 25.7 percent must be assumed for a non-grantor trust to win—but even then only for the first 20 years because a grantor trust would win each year thereafter).

15. IRC § 675(4)(C).

16. See, e.g., J. E. Smith and K. A. Curatolo, “Strategies for Mitigating the ‘Burn’ of Grantor Trust Status,” Bloomberg Tax (May 11, 2023). See also CA Probate Code § 15304(c) (effective as of 2023, requires express authorization in trust for reimbursement) and Ind. Code § 30-4-3-38 (effective as of 2024, states that unless the trust provides otherwise, the trustee may reimburse the deemed owner for income-tax liability).

17. IRC § 2036(a)(1).

18. See, e.g., G. Karibjanian, “Exploring the ‘Back-End SLAT’: Mining Valuable Estate Planning Riches or Merely Mining Fool’s Gold?” Bloomberg Tax Management Estates, Gifts and Trusts Journal 47, no. 6 (November 10, 2022).

19. See M. Merric and D. G. Worthington, “Best Situs for DAPTs in 2023,” Trusts & Estates (January 2023), https://www.wealthmanagement.com/estate-planning/best-situs-dapts-2023. See also K. Kamin and M. Seyhun, Introduction to Asset Protection and to Domestic Asset Protection Trusts, Illinois Institute for Continuing Legal Education (October 1, 2024), https://www.iicle.com/introduction-to-asset-protection-and-domestic-asset-protection-trusts.

20. See A. O’Connor, M. Gans, and J. Blattmachr, “SPATs: A Flexible Asset Protection Alternative to DAPTs,” Estate Planning 46, no. 3 (February 1, 2019).

21. See e.g., United States v. Grace, 395 U.S. 316 (1969) (applying the reciprocal trust doctrine where two trusts were interrelated leaving the settlors in approximately the same positions); Smaldino v. Comm’r, T.C. Memo. 2021-127 (finding the step-transaction doctrine where husband made gift to wife and she was merely intermediary).

22. For a detailed discussion of the arguments in favor and against this idea, see A. Bramwell and E. M. Mullen, “Donative Promise Can Use Up Gift Tax Exemption,” Steve Leimberg’s Estate Planning E-mail Newsletter #2001 (August 23, 2012); A. Bramwell, “The Gift-by-Promise Plan Works as Advertised,” Steve Leimberg’s Estate Planning E-mail Newsletter # 2033 (December 3, 2012); K. Heyman, C. McCaffery, and P. Schneider, “The Gift by Promise Plan SHOULD Work-At Least in Pennsylvania,” Steve Leimberg’s Estate Planning E-mail Newsletter #2034 (December 4, 2012); 33 P.S. Section 6 (a PA promissory note can be valid without consideration if the writing contains an express statement that the signer intends to be legally bound); J. Pennell and J. A. Baskies, “Final Words on Gift-by-Promise Technique,” Steve Leimberg’s Estate Planning E-mail Newsletter #2036 (December 10, 2012).